I had equal parts of anticipation and dread for this new adaptation of Patricia Highsmith‘s The Talented Mr Ripley especially as it was by schmaltzy Spielberg’s pal who wrote Schindler’s List and the film Hannibal. I take it all back: he read the book — or rather books as it became clear. Even better, he understood the book. Short version: I loved it. The cast: superb. Robert Elswit’s cinematography: divine. I even forgive the one ‘Schindler’ moment because it was a delight.

I always carp about people who refer to Tom Ripley as the ‘charming psychopath’: he is certainly the latter, but charming? I defy you to find me one place — oh wait. I did re-read the end of the novel after watching the final episode and there is actually one point where someone refers to him as ‘charming’ in a beautiful ironic moment where he is half-listening to an old woman gas on in order to distract himself from obsessive catastrophising thoughts. She calls him charming.

He is not charming: he is gauche and awkward and so self-unaware (especially about his own desires) — and this adaptation understands that and the arc of his story from timid would-be criminal to cynical successful criminal, albeit with an undercurrent of paranoia that it might all come crashing down at any moment, which he gets off on as much as it twists him in knots.

Spoilerific from here on: you have been warned. Also somewhat piecey and disorganised; unless someone wants to pay me to write something more formal, that’s how it will remain. Nobody wants to pay anybody for anything but capitalist waste.

Sexuality: it is an essential question. Previous incarnations of Ripley went with decisive choices: the aggressive heteronormative sexuality in Plein de Soleil, American Friend, Ripley’s Game and Ripley Under Ground, where Alain Delon, Dennis Hopper, John Malkovich (why his cameo made me laugh out loud with delight) and least convincingly of all, Berry Pepper, are positioned as oh you betcha straight men. [NB I will skip over Les Biches as a Ripley adaptation because that will derail this completely]. In contrast of course is the most popular adaptation, Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley, which makes him just as decisively gay.

All of these miss the slipperiness of Ripley’s sexuality, his aforementioned lack of awareness about himself (suggestive of an early tamping down of gay sensibilities like his author’s own) and how much of it has becomes fetishised around objects. The only real ecstasy in the book is when he is alone in the train compartment with all of Dickie’s stuff that is now his stuff and his bliss is palpable. He covets, and as Hannibal would ask us, how does he begin to covet? By what he sees. That’s why his taste is so execrable at first (though I love the paisley dressing gown). He learns to want better things. He learns so much with Dickie — like the Caravaggios. An excellent extrapolation that leads us through his transformation. People remarked on Scott being older than Ripley in the book, but it’s his gaucheness and ignorance that matter. He recognises quality once he begins to look for it, like Dickie’s pen (yes, how phallic LOL). It’s the looking that’s key.

Scopophilia: pleasure from looking. A key part of cinema/video and generally gendered. I think a lot of the people who were ‘bored’ by all the looking are reacting to a queer scopophilia of the series — how they can resist this gorgeousness shows you how strong the male gaze of the camera is fixed into our viewing habits. Ripley’s fetishised pleasure in things — art, pens, gleaming glass ash trays — and his pleasure in looking at Dickie combine for our complicity in looking at Ripley as he negotiates his way from clueless Bowery would-be grifter to confident killer. The camera becomes absorbed in watching Scott’s reactions as Ripley takes in all the new information and puts his talents to work. I think a lot of the people who find this ‘boring’ would not find it boring if the object of the camera’s gaze were someone like Lee Marvin, reflecting an untroubled mid-20 C masculinity back to the viewer.

At the risk of another Hannibal reference: this series has the effect his ‘field kabuki’ does on Will, bringing into sharp relief the difference between two versions of the ‘same’ murder. Minghella’s Ripley is so completely different despite its focus on making sure the narrative remains true to its queer roots. It’s a sun-soaked sensual film that softens everything, even Ripley. He doesn’t want to kill! In contrast the noir-infused black and white sharpness of the series keeps Ripley’s other queerness, his strangeness (likely reflecting Highsmith’s own probable autism) and masking that improves as his careful observation of everything sharpens its effectiveness — and feeds his greed for really nice things.

Another great example of the differences: Eliot Sumner v Philip Seymour Hoffman as Freddie Miles. Get a nepo baby to play a nepo baby and voilà! Sumner could not be more different than PSH’s über-macho closet case Freddie, full of brash bonhomie and possessiveness. Sumner has a Wildean liquidity and an aesthete’s flair. They make it possible to see the way that people on the margins of powerful groups tend to police the borders more avidly. They know they have risks and interlopers endanger their space. Hoffman’s Freddie is a player recognising a player. Sumner’s sees a direct threat in many ways to his relationship with Dickie.

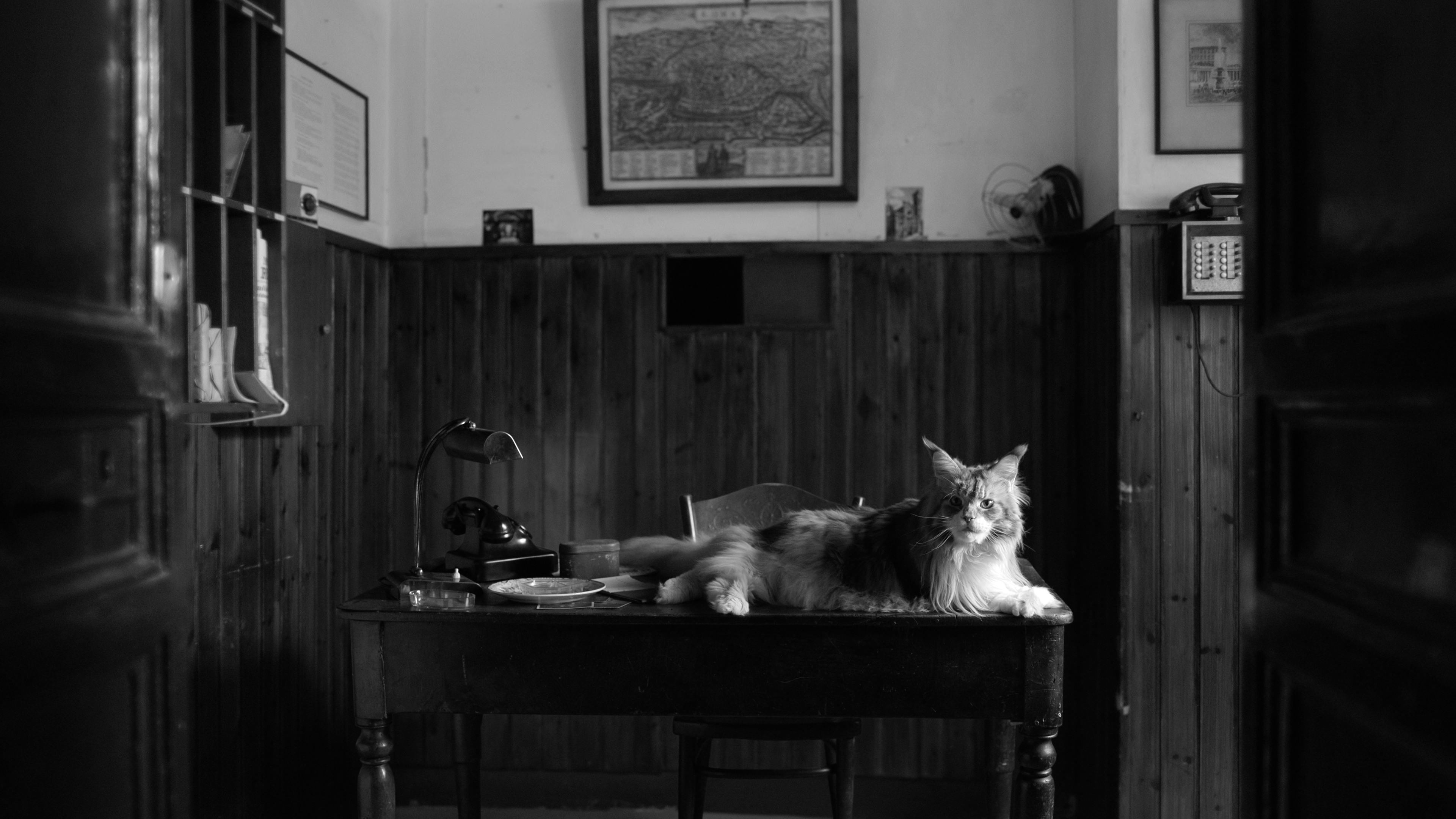

Cat: superb. No notes. Even made me forgive the one Schindler moment because it was hilarious.

Bokeem Woodbine: what a delight in a small role. It was interesting how they used the New York scenes to show a city that contained people of all nations and races, while the enclaves of the European rich are so very white. Somewhat disingenuous but a nice commentary, too, on notorious racist Highsmith’s flight to Europe (perhaps; I may see something there that others would shrug at).

Marge: a thankless role in so many ways. Fanning does very well with lots of interesting touches. Paltrow’s imperious take on the role focuses on her disgust at Ripley’s sexuality rather than much in the way of jealousy. Fanning makes sure we understand Marge as a middle class striver rather than another nepo baby like Dickie. Ripley’s contempt for middle class people, exacerbated by the time we reach the end of the novel, is rooted in his perception of them as in his way between his grinding existence and the beautiful ease he desires. Even the way Marge walks is interestingly specific. And she’s jealous of Ripley. She knows he’s more of a threat without understanding why. Once Dickie is out of the way, she is more friendly to him and his disgust with her at the party (I did like it changing to the Guggenheim house for my own scopophilic reasons) and afterward have as much to do with his disgust for feminine things in general (the way he shudders at the sight of her discarded clothing) as with her ambitious working. Rich people don’t work. They network.

Johnny Flynn’s Dickie: Ripley isn’t the only one uncertain about his slippery sexuality; the refrigerator incident tells us so much. Minghella’s Dickie is so firmly heterosexual he impregnates a seemingly random young woman in the village, but so accustomed to fawning that he doesn’t mind Ripley’s devotion as Marge does. Flynn’s Dickie is more enigmatic because he is more uncertain about life. Not the braggadocio would-be jazz musician but a truly bad painter who is not advancing because he won’t bend himself to be a humble student. And as his connection with Freddie emphasises, not completely unquestioning of his own sexuality. His experience shows when he shuts down Ripley’s innocent fun watching the acrobats on the beach, calling them ‘fairies’ and watching Tom’s face fall and then prevaricate about admiring the skills. He appreciates skill. Dickie does, too, but he doesn’t have the one he wants.

I could say a lot more but no one is paying me and soon I’ll be unemployed. I will have to stop giving away everything and figure out how to survive late stage capitalism.

ADDENDUM: How could I forget to mention le scale, le scale! Especially as we were joking about them so much while watching. The stairs may have been a bit on the nose re: class commentary but they were a great visual motif that was not immune to humour.